Ben Ali Ong – Ballads of the Dead and Dreaming

Art Month Blog 23/3/2011

Rhianna Walcott

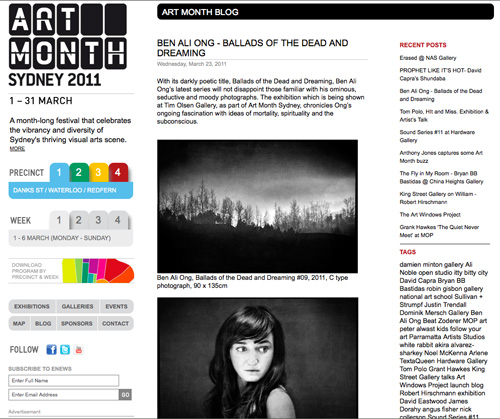

With its darkly poetic title, Ballads of the Dead and Dreaming, Ben Ali Ong’s latest series will not disappoint those familiar with his ominous, seductive and moody photographs. The exhibition which is being shown at Tim Olsen Gallery, as part of Art Month Sydney, chronicles Ong’s ongoing fascination with ideas of mortality, spirituality and the subconscious.

Moving through the exhibition, the viewer slips between images of bare wintry landscapes, tempestuous seas and birds circling against a backdrop of brooding apocalyptic clouds. Interspersed amongst these landscapes is a series of tableaux, featuring antiquated marble figures and scenes from long forgotten paintings, set side by side with portraits depicting ghost like figures. Wreathed in mystery and ambiguity, each photograph taps into the subconscious of the viewer, provoking a myriad of different associations and unique emotional responses.

Recognisable by their distortions and imperfections, Ong’s photographs carry obvious reminders of the artist’s existence and involvement in the creative process. Shot with an analogue camera on 35mm black and white film, the artist deliberately sets out to physically manipulate each image and has been known to scratch and mark the surface of the negative with etching tools, sandpaper, water and chemicals amongst other things. The resulting distorted negatives are then layered and sandwiched together during the scanning process to produce photographs which capture a timeless, dreamlike quality.

The inherent allure of Ben Ali Ong’s photographs stems from the psychological pull which draws the viewer into each work. Influenced by artists such as Francis Bacon, Goya and early French Impressionist photographers and reminiscent of film noir imagery, Ong’s work has an underlying sense of anguish and sorrow (perhaps even horror) which clings to these black and white photographs. The shadowy, brooding drama and chiaroscuro of the artist’s work captures the delicate interplay between lightness and darkness in a way which acts as a visual metaphor for the vagaries of human existence; alluding to the idea that the beauty and fragility of life are inseparable from the horror and sorrow which accompany it. The resulting emotional pull resonates with and touches some deep inner core which resides within all humanity, transporting us away from our everyday existence.

Ong’s portraits seem to capture a moment outside of time in which the subject of the portrait is both present and absent. With their blurred faces, haunted eyes and almost terrible stillness, Ong’s portraits are reminiscent of memento mori, eliciting reminders of the fragility of the individual. Captured on film, the anonymous subjects of these portraits appear to be almost fading away before our eyes whilst, in contrast, the anguished face of a woman carved from marble possesses a sense of movement and life noticeably absent from the portraits of the living. In this way, Ong’s photographs, which are at once both beautiful and frightening, achieve a timeless, unknown, almost half forgotten quality or existence which touches upon ideas of life, death and morality.

Perhaps the most powerful element of Ben Ali Ong’s practice though, is the fact that, unlike many contemporary artists who find themselves caught in a web of intellectualization, Ong’s photographs speak straight from the soul…

Rhianna Walcott is an arts writer and gallery manager of Artereal Gallery, Sydney

All images courtesy of the artist and Tim Olsen Gallery, Sydney

Songs for Sorrow

Better Photography Summer 2011

What does it take to become an art photographer? While well-known artists can command high prices for their work, most started with small shows and built their reputation over number of years. Ben Ali Ong is at the beginning of his career, having just secured representation with the Tim Olsen Gallery in Sydney where at his first exhibition with the gallery he sold 22 pieces.

Insight

Ben was introduced to photography while at school. His sister was modelling and doing figure work for art photographers, including well-known photographer and educator, Professors Des Crawley. Ben explains that he went along to a few photo sessions as a typically disillusioned teenager, but found it interesting, especially the black-and-white infrared film Des was experimenting with.

“Des really helped me out, teaching me darkroom printing techniques and after high school he suggested a TAFE course. I did a Diploma in Photography part-time at Ultimo and started work with Warren Macris where I learnt the digital side of photography.”

Becoming an art photographer isn’t matter of applying for a job, rather you have to build a reputation by exhibiting your work.

“It can sound a little pretentious to say you’re an art photographer, but I’m not a commercial photographer and nor am I a painter. I guess I’m a photo-media artist, but it doesn’t really matter what I’m called.

“I’ve never been interested in wedding or commercial photography. What struck me about Des’s work was that it was always more aesthetically based and this is what appeals to me.”

Ben admits that statistically art photography is not a high value career, but he loves it too much to let it bother him. “I’m too far down the road to turn back and as long as I have a part time job, I’ll be okay. I have a few friends who work full time as artists and I hope to get there one day.”

So what does it take to be a successful as an art photographer? What steps do you need to take?

“I don’t know if there are any rules, but certainly people need to be able to tell that a photograph is yours. You need to develop your own recognisable style, your own voice, but at the same time your work needs to change and develop.

Influences

Ben’s style is dark and brooding, similar he suggests to a black-and-white 1920’s film noire. “I really like the early pictorial photographers with all the little imperfections in their work. Even though they were not intentional, there’s a beauty in these errors and I like my work to feel like that.” Ben references the work of Antoine d’Agata, a Magnum photographer with a style that seems to defy Magnum’s own genre. “ I was really blown away by his work – it’s nice to know that when everyone seems to have done it all, someone comes up with something new and different.”

Ben also admires the work of Bill Henson and David Noonan, the latter who works with collages in a sculptural way. I also love the whole Japanese photography movement, especially the black and white photographers with their darker sensibility. Sometimes the work is macabre, but its not a gimmick, rather a reflection of the Buddhist embrace of death. There’s something about the work of photographers like Eikoh Hosoe that has a spiritual connection when I look at it. It could just be a cultural thing, but even the way they technically print their work appeals to me.”

Songs for Sorrow

“Most of my work is pretty dark,” Ben admits. He has a quote by Joseph Campbell that resonates with him:

One thing that comes out in myths is that at the bottom of the abyss comes the voice of salvation. The black moment is the moment when the real message of transformation is going to come. At the darkest moment comes the light.

“For me, it’s quite easy to take a beautiful photograph of a landscape, but there’s more to it. It’s a balance between the light and the dark, at least, that’s what I have found to be the most powerful for me.

“There’s a need in the art world to over intellectualise the work that’s exhibited, but I think most artists work comes from their soul. I could go on about a disjointed narrative, but the reality is its just me and my own little black and white story. “

The title of Ben’s exhibition, Songs for Sorrow was inspired by the Sorrowful Songs symphony by Henryk Gorecki. “Music is also a source of inspiration. In fact, it’s one of the main ones and I always have music playing with I’m working.”

The second image in the exhibition (titled Songs for Sorrow #02) was the most popular. “It really struck a chord with people. I thought that portraits were traditionally harder to sell than a landscape, but what do I know?” The full impact of the work comes when you see it full size, not as a small reproduction in a magazine. The appeal, Ben believes, was because the subject, his sister, was blinking at the moment of exposure. This, combined with a slow shutter speed of around 1/15 second, created a blur over the eyes.

Film Capture

“I was visiting my parents last Christmas and my sister had her hair done for a 1950’s Rockabilly thing, so I asked if I could take her picture. I sat her in front of a mahogany bed boar with window lighting- terrible conditions for a portrait – and used a 50mm f.18lens. The first frame has her looking left and slowly turning her head over her shoulder, and that’s the one with her eyes a bit blurry. I don’t know why it works so well!”

Ben enjoys working with film, in this case Kodak T-Max ISO 400. I use the same Nikon F100 I used through TAFE and a film scanner. I like the way film makes the image appear quite grainy, especially when printed large. It’s not that I don’t like shooting with digital, rather I have an approach that works for me, so I stick with it. I know you can probably replicate the grain digitally, but I don’t believe people care how it is shot.

“I used to analyse everything in a photograph, but I think it’s easy to get caught up with the technology. From the little I know about the art world, people just don’t care about how a work is created. In fact, I think some people who saw my exhibition believe my works were etchings.

“Growing up in the photographic world we become quite technical, but these things that only other photographers see. For instance, I don’t believe it matters what our work is printed on, unless you’re aiming for specific collectors of traditional photography. In the contemporary art world, it simply isn’t important.”

Textures & Layering

Ben often scans his negatives through a thin sheet of tracing paper, or a sheet of tracing paper, or a sheet of clear acetate that has been left in the sun to produce a slightly foggy effect. He also layers textures over his images in Photoshop, such as droplets on a shower mirror or paint splatters.

“I used to scratch the negative using etching tools or a sanding block to produce very slight sanding. You can barely see it on the negative, but when printed up larger it gives an impressionist look. I like the image to look a little damaged, but the effect shouldn’t be too obvious.

“Early impressionist photography had lots of small imperfections and although the photographers probably hated the result, for me there is something that gives them a timeless quality.”

The image after scanning when sandwiched with tracing paper is very flat, so Ben increases the contrast in Photoshop and darkens the image down. When happy with his work, 120 x 80cm exhibition prints were produced.

“It’s amazing what you can get away with when using film. In fact, this is what I like, the way the image starts to fall apart as you enlarge it.

Persistence Pays

When Ben first approached galleries to exhibit his work, he had little success, but he discovered a number of small artist-run spaces where anyone can have a show.

“It’s a bit like being a musician – you have to perform even if its only a pub gig. Performing helps you develop a style and the more you perform, the more people recognise you. Even if you exhibit with little success, at least people know you are practising. You have to keep slugging away.

“Then I got lucky. The Tim Olsen Gallery saw my work and asked if I wanted to join. The Gallery represents mainly artists and I’m the only guy who does photography. The deal is one show a year with an opening and hopefully we both make some money! The first show in May this year worked out well and my next show is in March 2011.”

With a gallery behind you, the mechanics of hosting an exhibition are relatively easy for the photographer. Ben simply creates the work to hang, but that’s it. My job is to make he work and their job is to get it out there.

“The gallery also handles the publicity, prints flyers, produces invitations, organises the catalogue and so on. I’m so glad I don’t have to do that anymore!”

Ballads of the Dead and Dreaming

Gone at Dusk 2011

Well I’m always influenced by music, my last series was called ‘Songs for Sorrow.’ My friend Ray Cook said there is a musical quality in my work in that they can be rearranged and reinterpreted to take on different meanings, I really liked that. There is no real order to my images, when I have a body of work up in an exhibition it can be quite disjointed, some people don’t like that. But i think if you don’t focus so much on the lieral meaning of things, you can defiantly sesnse a unison of mood throughout the work.

I understand you’re very interested in 1920’s film noir. How did photography become a road of exploration for you?

Yeah i love old black and white movies, any old movies really. I was reading once the surrealist film makers in the 20’s in Paris, apparently they used to go into the cinemas at random parts of the films and as soon as they would figure out what the story was about they would leave and go onto the next one. That stuck with me so strongly, I love the idea that the mystery was more important than they story and how they chased that excitement of the experience of revelation. I started photography in high school and just really fell in love with it I suppose. I always wanted to be an artist of some sort, I wanted to be either a poet or a trumpet player so not sure why I ended up with Photography!

You are known for using a range of techniques to scratch and distort your photographs. Could you tell us about your approach to making such images? Do you have a finished result in mind, or do you allow the technical imperfections to take over the work?

Well I’m not doing all that stuff so much these days. Actually I am, it’s just pulled back a lot more than it used to be. Because I have been doing this treatment to the negatives so many times I can look at something now and pretty much know how I will mess it up and distort it, but when I started I was just having fun and playing around. I’m much more controlled with it now. I’ve also learnt that sometimes the images don’t need anything done to them at all, and sometimes I will really get in there. Basically I’m just trying to recreate the beauty of imperfection, but in a more controlled manner I guess. Van Morrison saids it’s the cracks that let the light shine through.

I recently visited you solo exhibition at the Edwina Corlette Gallery in Brisbane. Moving through the exhibition was like living in the midst of a deep, uneasy breath. You could feel the dampness of death thicken around you. You seem to be fascinated by death, spirituality and subconscious. What is it about these ideas that interests you?

I’m glad you got it. Well like I said I’ve always been attracted to the darker side of things. I guess I went through a rough time in my life too and I started making these really heavy images, it’s eased up a lot over the years, the darkness is still there, it’s just more refined I think. If anything it’s more powerful now because it’s subtle. Iv’e always been fascinated with the sky, with space, with mythology, the more I started reading the more I learned that all these things are interconnected. Our experience as human beings on this planet, I just believe there is so much more to what we think is reality, we are like a civilisation with amnesia. I like how photography plays with this idea a bit, it’s reality but at the same time it’s not. What re these images we see and how do they relate to time and place after they are taken and presented in different contexts? And what is this world I am creating?

Your photographic style is very unique. You seem to create a sense of fantasy and mysterious relationships between different subjects. What have been the main influences over you and your work?

Thank you. My main influences? Life. Emotion; love, anger, depression, joy. Surrealism is a big influence, the film makers or that period like I said. The writers also. I was reading how they used to tear a page in 4 pieces then rearrange it randomly to create new depth and meanings to the work. It’s a similar approach I think to how I create the different relationships between different subjects like you said. I love all the Japanese photographers. Nobuyoshi Araki said black and white photography is like death. I love the French photographer Antoine D’agata. Jimmi Hendrix and Nina SImone are big influences. I love Bill Henson. My favourite artists of all time is Francis Bacon and also Cy Twombly… R.I.P.

Some artist’s work has the capacity to take you places that most never can, transporting you to allegorical destinations using poetry as its fuel. Ben Ali Ong’s imagery circumvents those stubborn inadequacies of the often clumsy language we utter, crafting vocabularies to address the sublime. There are no words to convey certain feelings with any real precision; certain frames of mind, the way the heart feels when it beats in sullen empathy or despair; those moments that have no materiality in real world though they animate the mind. To pin these elusive things down, to still them for our scrutiny, the camera must be an instrument not just a tool; to evoke and not simply record. Ben blends portraits and landscapes, layering textures of history against the uncertain possibilities the future presents, bringing about the genesis of a remarkably convincing new world. He anticipates those collective anxieties that haunt us all in this age of spiritual abandonment – culpability for the atrocities of the past, life’s frailty, love’s ultimate futility, the finality of death. He orchestrates these frighteningly beautiful images to confront the terrifying question we’d all rather deny, “What does the world hold for us when it’s deserted by the divine”.

Ray Cook

Lecturer, Queensland College of Art, 2012